Copper and its alloys play a critical role in modern manufacturing. Whether used in electrical conductors, heat-exchange systems, high-temperature components, or parts that require welding and machining, the melting point of copper directly influences processing methods, heat-treatment strategies, joining procedures, and long-term service performance.

This article explains the melting point of copper, the factors that influence it, the melting ranges of typical copper alloys, and how melting behavior affects practical manufacturing and machining decisions.

What Is the Melting Point of Copper?

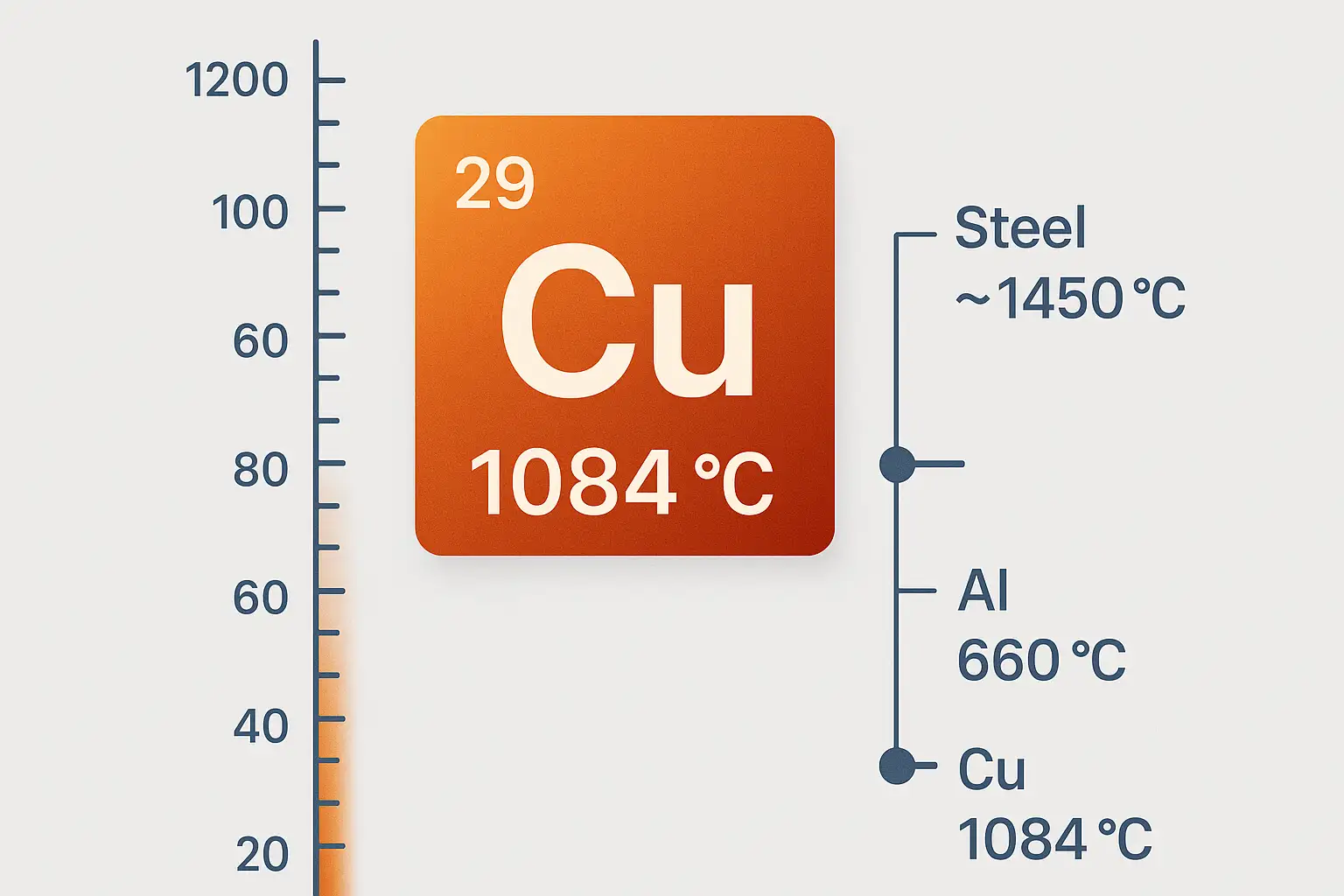

Pure copper (Cu) has a melting point of approximately 1084–1085 °C (≈ 1984 °F) at standard atmospheric pressure (≈ 101.3 kPa). Some technical references state 1084.62 °C, but 1084 °C is widely used in engineering.

The melting point is not a processing temperature. Machining and most heat-treatment operations never approach this value, but the melting point defines the upper boundary for welding, brazing, and structural stability.

Why Does Melting Point Matter in Manufacturing?

The melting point acts as a thermal boundary that defines how copper and its alloys behave under heat during processing and service conditions. Its influence becomes clear when examined across different engineering scenarios.

Material Selection and High-Temperature Service

A material’s melting point determines whether it can operate in high-heat environments such as heat exchangers, steam systems, and high-temperature electrical conductors. For comparison, tungsten melts above 3400 °C, making it extremely heat-resistant, while copper and gold melt near 1084 °C and 1064 °C, limiting their suitability for extreme heat exposure despite their stability.

Welding and Brazing Temperature Control

Copper components are commonly joined by brazing or silver soldering. Joining temperatures must remain below the melting range to avoid collapse or oxidation. Weldability is also not determined by melting speed. Although copper (~1084 °C) and gold (~1064 °C) melt at similar temperatures, their joining behavior depends far more on oxidation tendencies and alloy chemistry than melting rate.

Heat Treatment and Grain Stability

Heat-treatment temperatures must remain well below the melting point to prevent grain coarsening or partial surface liquefaction. Copper alloys are typically annealed between 200–600 °C, far below their melting ranges.

Applications of Copper Melting Point in Manufacturing

The melting point of copper directly guides several practical decisions in industrial production. Its impact becomes clearer when applied to specific processes and component requirements.

Selecting Joining Methods

Brazing, silver soldering, or TIG/MIG welding is chosen based on how close the joining temperature can approach the melting range without damaging the part.

Predicting Casting Behavior

Alloys with narrower melting ranges exhibit faster solidification and less segregation, while wider ranges influence fluidity, shrinkage, and defect risk in mold filling.

Controlling Heat During Multistep Manufacturing

Processes such as forging, welding, and post-machining must be planned so that heating cycles never approach the softening zone created below the melting point.

Choosing Materials for Heat-Exposed Components

Components such as heat exchanger plates, high-current connectors, and induction coils require alloys whose melting and softening ranges align with operating temperature limits.

This transforms melting point from a theoretical property into a tool for engineering decision-making.

What Affects the Melting Point of Copper?

Different formulations and metallurgical environments can shift the melting range or convert a single melting temperature into a broader transition zone. These influences can be grouped into alloy chemistry, purity level, and processing conditions.

Alloying Elements

Alloying modifies the crystal lattice and changes melting behavior, creating a melting range instead of a single point.

- Brass (Cu–Zn): Lower melting range; zinc evaporation risks at excessive temperatures.

- Bronze (Cu–Sn): Enhanced wear resistance; melting range varies with tin content.

- Copper–Nickel (Cu–Ni): Some grades melt slightly above pure copper.

- Beryllium Copper (Be–Cu): Lower melting range but exceptional strength and elasticity.

Purity and Impurity Levels

- Higher purity produces a more defined melting point and narrower melting interval.

- Impurities such as sulfur, oxygen, or lead lower the melting point and widen the melting range, affecting casting fluidity and welding quality.

Pressure and Metallurgical Environment

- Higher pressure slightly raises melting point; reduced pressure lowers it.

- In powder metallurgy, very fine copper particles can display lower apparent melting characteristics, which mainly matters for sintering.

How Does Copper’s Melting Point Compare with Other Metals?

| Metal | Melting Point (°C) | Engineering Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | ~660 | Supports low-temperature casting and brazing; low energy input |

| Copper | ~1084 | Requires mid-high joining temperature; unsuitable for low-temp casting |

| Steel (Carbon/Alloy) | ~1450–1520 | Requires high-capacity furnaces; high welding heat and energy demand |

Result: Copper requires more heat than aluminum but significantly less than steel, influencing furnace selection, joining temperature, and casting method.

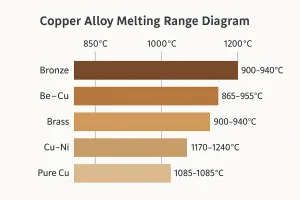

Melting Ranges of Common Copper Alloys

| Copper Material | Typical Melting Range (°C) | Notes / Industrial Use Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Copper (Cu) | ~1084–1085 | Stable melting point; high thermal conductivity |

| Brass (Cu–Zn) | ~900–940 | Zinc lowers melting range; risk of Zn vaporization if overheated |

| Bronze (Cu–Sn) | ~850–1050 | Range varies with Sn content; stronger wear resistance |

| Copper–Nickel (Cu–Ni) | ~1100–1240 | Higher melting range; excellent corrosion resistance for marine use |

| Beryllium Copper (Be–Cu) | ~980–1000 | Lower melting range; exceptional strength and elasticity |

Exact values vary by alloy grade and standard; consult datasheets for precise engineering specifications.

How Copper Is Melted in Manufacturing

Copper and its alloys can be melted using different heating methods depending on batch size, purity requirements, and chemical control. The most common industrial melting processes include the following:

1.Induction Melting

Provides stable, uniform heating with low contamination risk. Commonly used for precision copper alloys requiring tight chemical control.

2.Crucible Melting

Suitable for small to medium production batches. Crucible material (graphite, clay-graphite, silicon carbide) can influence copper purity and alloy chemistry.

3.Electric Arc Melting

Used for high-purity or specialty grades. Capable of very high temperatures but requires careful control to avoid oxidation.

4.Vacuum or Plasma Melting

Minimizes oxidation and prevents vaporization of volatile elements such as zinc in brass. Ideal for aerospace and high-performance copper alloys.

Copper should not be overheated during melting, as excessive temperature can cause alloy vaporization (especially zinc in brass) and increase oxide formation. Fluxes or shielding atmospheres are often used to protect molten copper during processing.

Conclusion

Copper melts at approximately 1084 °C, but its melting behavior changes significantly with alloying, impurities, and melting conditions. These variations influence casting flow, welding temperatures, heat-treatment planning, and machining stability. For components exposed to welding, heating, or precision machining, controlling melting behavior helps ensure reliable performance and long-term dimensional stability.

🔧 Need machining or welding support for a specific copper alloy? Share your drawings and grade specifications for engineering guidance.