When facing deep slots that challenge vertical accuracy, side milling serves as the high-rigidity solution of choice. Achieving the perfect balance between efficiency and precision requires mastering specific technical variables. This guide breaks down the working principle, key quality factors, and essential tool types.

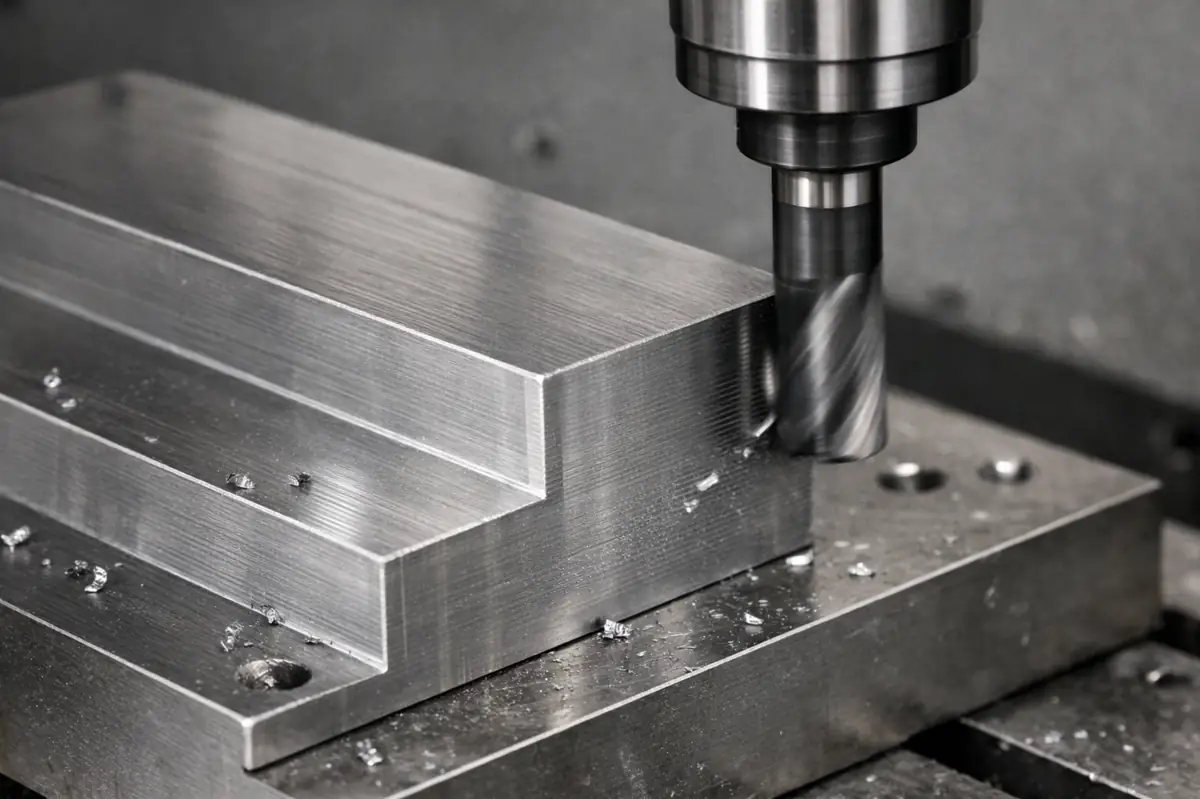

What Is Side Milling?

Side milling is a high-precision machining process that utilizes the peripheral cutting edges of a milling cutter to remove material. The fundamental distinction from standard end milling lies in its mechanical configuration—it typically employs a horizontal arbor to provide dual-point support, transferring cutting loads directly along the machine spindle’s most rigid axial path. This unique force distribution mechanism grants side milling unparalleled vibration resistance and trajectory stability when processing deep, narrow slots, long-travel paths, and complex stepped surfaces.

In industrial practice, side milling is more than just an efficient material removal method; it is a strategic solution for achieving extreme geometric tolerances. By configuring multiple cutters on a single arbor, the process enables “single-pass, multi-surface” machining. This physically ensures absolute positional accuracy and batch consistency between various part features, far exceeding the capabilities of sequential machining.

How Side Milling Works?

Side milling is driven by a horizontal arbor secured between the spindle and an overarm support. This “two-point support” structure, similar to a bridge, physically eliminates the vibration risks of cantilevered setups, providing a high-rigidity foundation for heavy-duty cutting.

During operation, peripheral teeth rotate around the horizontal axis to engage the material sequentially. This radial loading pattern transfers cutting forces directly to the rigid arbor, preventing tool deflection during deep slotting or long-travel passes. This stable cutting action is the core principle behind ensuring sidewall verticality and linear consistency.

For complex profiles, side milling utilizes precision spacers to lock multiple cutters onto a single arbor for synchronized operation. This “single-pass” process ensures that the geometric relationship between different surfaces is mechanically fixed, fundamentally eliminating the cumulative errors caused by multiple setups.

What Are the Factors Affecting the Quality of Milling?

Arbor Sag and Lack of Rigidity

Gravity naturally causes horizontal arbors to sag slightly. If the overarm support is misaligned or the arbor is excessively long, the resulting slots will lose their verticality, leading to tilted sidewalls. Regularly calibrating the parallelism between the arbor axis and the machine table is the primary solution to ensure squaring accuracy.

Excessive Radial Runout

Minor eccentricity during tool assembly causes uneven loading on the cutter teeth, which generates noticeable chatter marks on the workpiece surface. Using high-precision ground spacers and ensuring all mounting surfaces are clean are critical for minimizing runout and achieving a superior surface finish.

Poor Chip Evacuation

When machining deep slots, chip accumulation often leads to “re-cutting” or sudden tool edge chipping. Leveraging the centrifugal force of the rotating cutter, combined with high-pressure coolant to flush chips out of the cutting zone, is essential for maintaining a clean and consistent surface texture.

Entry Deflection and System Instability

Unstable forces at the moment the tool engages the material can cause the dimensions to drift. Prioritizing a Climb Milling strategy—which directs cutting forces downward into the table—significantly enhances system rigidity, prevents tool deflection, and ensures tight geometric tolerances.

Types of Side Milling Operations

Side milling is categorized by the specific configuration of the cutters and the geometric features they produce. By adjusting the arbor setup and tool selection, we execute several distinct operations to meet diverse engineering requirements and production scales.

Slotting and Grooving

Slotting is the primary form of side milling, utilizing a cutter with teeth on its circumference and both sides to create precise channels. In this operation, the tool is engaged on three surfaces simultaneously, requiring expert chip management. We utilize this method for machining keyways and T-slots, as it provides superior verticality and width control compared to standard end milling, particularly in deep-reach applications where tool deflection must be avoided.

Straddle Milling

Straddle milling involves mounting two side milling cutters on a single horizontal arbor, separated by a precision-ground spacer. This setup allows for the simultaneous machining of two parallel vertical surfaces in a single pass. It is the industry-standard choice for manufacturing clevises, slide blocks, and symmetrical tongues, where maintaining perfect parallelism is critical. By finishing both sides at once, we eliminate the cumulative errors caused by multiple setups and ensure consistent accuracy across large batches.

Gang Milling

Gang milling is a high-efficiency operation where three or more cutters of varying shapes and sizes are “ganged” together on the same arbor to machine a complex profile in a single stroke. This technique is strategically used for the mass production of structural components featuring multiple steps, flats, and grooves. While the initial engineering setup is highly specialized, it results in unmatched profile consistency and a significant reduction in the overall cost per part.

Half Side Milling

Half side milling utilizes cutters with teeth on the circumference and only one side, specifically designed for machining a single vertical shoulder or the periphery of a part. Because the tool is optimized for single-sided engagement, it offers exceptional rigidity under heavy lateral loads. This is the ideal process for squaring up large blocks or machining heavy-duty mounting pads, ensuring a flat, perpendicular finish without the risk of tool vibration or surface chatter.

Slitting and Sawing

Slitting is a specialized operation that uses thin-profile cutters (slitting saws) to create narrow slots or to part a workpiece into sections. By utilizing the high torque of a horizontal milling machine, we can achieve deep, narrow cuts with minimal kerf loss. This method is far more efficient than other techniques for producing heatsink fins or performing deep parting operations on large castings, as it maintains a perfectly straight cutting path while minimizing material waste.

Types of Side Milling Cutters

Choosing the correct cutter is the most critical factor in achieving the desired tolerance and surface finish. Depending on the material hardness and part geometry, our engineers select from several specialized tool geometries to optimize the cutting process for maximum efficiency.

Lineup of plain, staggered, half-side, interlocking and indexable side milling cutters on a machine table.

1. Plain Side Milling Cutters

Plain side milling cutters are the standard choice for general peripheral machining, featuring cutting teeth located only on their circumference. These tools are specifically engineered to provide a clean and continuous cutting action on flat side walls. By ensuring a seamless sweep along the workpiece, they produce a superior surface finish that is often required for aesthetic components or final finishing passes where surface integrity is paramount.

2. Staggered Tooth Side Milling Cutters

For more demanding applications, we utilize staggered tooth side milling cutters which feature alternating or “cross” flute angles. This specialized geometry is designed to handle much heavier cutting loads while maintaining long-term dimensional consistency. The staggered arrangement effectively breaks up metal chips and dampens vibration, allowing the tool to maintain precise slot widths and perfect verticality even when machining deep profiles in tough alloys.

3. Half Side Milling Cutters

Half side milling cutters feature cutting teeth on the circumference and only on one side of the face. This specific design offers exceptional rigidity when machining a single vertical step or shoulder. They are frequently used in “straddle milling” setups, where two cutters are mounted on the same arbor to machine two parallel surfaces simultaneously, ensuring high efficiency for industrial components.

4. Interlocking Side Milling Cutters

Interlocking side milling cutters consist of two sections that fit together to form a single unit. This design is particularly valuable for maintaining consistency over long production runs. By adding thin shims between the interlocking sections, we can precisely adjust the tool width to compensate for dimensional changes after the tool has been sharpened, ensuring the slot width remains perfectly within tolerance.

5. Carbide Tipped & Indexable Cutters

In modern high-speed CNC machining environments, carbide tipped and indexable cutters have become the industry gold standard. Because carbide materials can withstand much higher temperatures, they allow us to significantly increase spindle speeds and feed rates compared to traditional steel tooling. This not only shortens overall production cycles but also offers a significant cost advantage, as worn cutting edges can be quickly refreshed by simply indexing or replacing the inserts.

Pros of Side Milling

Side milling is a cornerstone of precision manufacturing, offering unique benefits that face or end milling cannot always provide. By utilizing the peripheral edges of the cutter, this process ensures superior results for specific geometric requirements:

- Superior Vertical Accuracy: The use of the cutter’s circumference allows for the creation of vertical walls with exceptional perpendicularity to the base, maintaining tighter tolerances for high-precision components.

- Enhanced Surface Integrity: Because the side edges produce a more consistent cutting path, the resulting surface finish is more uniform with fewer tool marks, making it ideal for parts where aesthetic quality is paramount.

- Efficient Deep-Feature Machining: Paired with specialized long-reach tooling, side milling can effectively process deep slots and high vertical profiles that would otherwise be unstable or impossible for other milling methods.

- Improved Tool Longevity: By distributing cutting forces along a longer portion of the cutting edge rather than concentrating heat at the tool tip, side milling reduces localized thermal stress and extends the overall life of the carbide tool.

Cons of Side Milling

Despite its strengths, side milling is a sensitive operation that requires careful engineering oversight. Understanding its limitations is essential for avoiding quality issues and managing production costs effectively:

- High Demand for Machine Rigidity: Side milling generates significant lateral forces; if the machine spindle or setup lacks sufficient rigidity, “tool deflection” can occur, leading to tapered surfaces and dimensional errors.

- Challenging Chip Evacuation: In deep or narrow slotting operations, metal chips often become trapped. Recutting these chips can lead to surface marring, excessive heat, and potential tool failure.

- Risk of Thin-Wall Deformation: The lateral pressure inherent in side milling can cause thin-walled parts to flex during machining. This often results in a “spring-back” effect once the part is released from the fixture, affecting the final precision.

- Higher Tooling Expenses for Tough Alloys: Processing hardened steels or titanium via side milling puts immense thermal load on the tool. This necessitates the use of premium coatings and high-performance cutters, which increases the per-part manufacturing cost.

Side Milling vs Face Milling vs End Milling

While all three processes are performed on a milling machine, they differ significantly in terms of the cutting surface used, the material removal rate, and the intended application. Understanding these differences is key to selecting the most efficient machining strategy for your project.

| Feature | Side Milling | Face Milling | End Milling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cutting Edge | Peripheral Edges (Side) | End Face (Bottom) | Both Side and Bottom |

| Main Goal | Vertical Walls & Slots | Surface Flatness | Complex Cavities & Shapes |

| Surface Finish | Vertical Texture | Circular/Swirl Patterns | Mixed Patterns |

| Material Removal | High (for vertical depth) | Very High (for surface area) | Moderate & Versatile |

To help you decide which method fits your design, here is a detailed breakdown of how they compare:

- Side Milling vs. Face Milling: Face milling focuses on the “top” surface of the part to achieve perfect flatness using the bottom of the tool. In contrast, side milling uses the side of the tool to machine vertical “walls.” If you need a smooth floor, choose face milling; if you need precise vertical sides, side milling is the answer.

- Side Milling vs. End Milling: End milling is the most versatile, as the tool can cut with both its end and its sides to create pockets or holes. Side milling is technically a specific application of end milling that prioritizes the use of the tool’s diameter to sweep along the outer or inner perimeters.

- Choosing the Right Method: For high-volume production, we often combine these methods—using face milling for the base, end milling for internal pockets, and side milling for the final high-precision contouring of the external walls.

When to Use Side Milling?

While end milling is widely used in modern machining, side milling remains the superior choice in specific engineering scenarios due to its exceptional rigidity and multi-cutter versatility. The process provides significant technical advantages when project requirements focus on the following criteria:

Parallelism and Symmetry

If a component design demands high parallelism or symmetry between two opposing surfaces, such as in clevises or slide blocks, the straddle milling approach is irreplaceable. Unlike machining each side in separate setups, this method can eliminate cumulative errors caused by repositioning, physically guaranteeing absolute parallelism between the two faces.

Deep Slotting

In deep and narrow slotting operations, standard end mills often suffer from deflection due to excessive tool overhang, leading to out-of-tolerance widths. Because side milling cutters are mounted on a high-rigidity horizontal arbor supported at both ends, excellent verticality can be maintained even under heavy cutting loads. This makes it the ideal process for precision keyways and high-aspect-ratio grooves.

Complex Profiles

For the mass production of structural components featuring multiple steps, grooves, or specialized flats, utilizing a single tool for multiple passes is highly inefficient. Through gang milling, multiple operations can be integrated into one, exponentially increasing throughput while ensuring that thousands of parts maintain identical profile dimensions and unmatched consistency.

Heavy Material Removal

When machining large bases or the edges of heavy castings, side milling can withstand much higher cutting loads. Since side milling cutters typically feature wider cutting edges and are supported by the high torque of a horizontal spindle, they are far more efficient for heavy-duty roughing than end mills, and tool life can be significantly extended in the process.

Narrow Slitting

For applications requiring part separation or the creation of narrow gaps with minimal material waste, such as heatsink manufacturing, slitting saws are the most efficient solution. This process can achieve minimal kerf loss while ensuring the vertical integrity of the cut does not drift as depth increases—addressing a common challenge for other machining methods.

Process Challenges and Solutions

Achieving peak precision in side milling requires a deep understanding of cutting mechanics. The inherent technical hurdles of the process can be effectively managed through refined engineering strategies and real-time process control.

Surface Chatter

In deep-reach grooving, the large contact area between the cutter and the workpiece can trigger high-frequency harmonic resonance, resulting in visible chatter marks. This can be mitigated by utilizing staggered tooth cutters, which break the periodicity of cutting forces to cancel out vibration. Combined with optimized arbor rigidity, this ensures a mirror-like sidewall finish even in high-aspect-ratio slots.

Structural Deformation

When machining thin-walled or slender components, the lateral cutting loads of side milling can cause physical part deflection. The most effective strategy is the use of straddle milling with symmetrical cutting forces, where two cutters engage the workpiece simultaneously from opposite sides. This balanced force approach maintains the part’s structural neutrality and ensures strict linear tolerances in delicate geometries.

Chip Evacuation

Poor chip removal in narrow gaps is a primary cause of surface scratching, compromised finishes, and premature tool failure. Beyond high-pressure coolant systems, the process can be optimized through strategic cutting directions, such as climb milling, to guide chips away from the cut. By precisely controlling feed rates to ensure consistent chip breaking, metal residue is prevented from re-cutting, protecting the integrity of the slot base.

Cumulative Tolerance Error

In complex gang milling setups, micro-gaps between multiple cutters and spacers can lead to significant tolerance accumulation. To maintain profile consistency, the risks can be minimized by exclusively using hardened, precision-ground spacers with parallelism tolerances within 0.005mm. Before mass production, performing CMM (Coordinate Measuring Machine) scans on the first article allows for micron-level calibration of the cutter assembly.

Thermal Drift

Prolonged, heavy-duty milling generates significant heat, causing tool expansion and subtle dimensional drift. This can be managed through a combination of full-synthetic internal cooling and a tool-life monitoring system. By proactively replacing tools before the wear-induced temperature spike occurs, dimensional fluctuations are locked within a highly controlled range over long production cycles.

What Are the Applications of Side Milling?

Side milling is a vital process for manufacturing critical mechanical components.

By leveraging high-rigidity setups, this technique is utilized to produce a wide range of industrial parts with high precision:

Drive Shaft Keyways and T-slots

Side milling is the standard process for machining precision keyways, slide slots, and T-slots in power transmission systems and machine tool tables. It ensures consistent slot width and sidewall verticality, meeting strict assembly tolerances for shafting components.

Connecting Rods and Clevises

This process is extensively used for producing automotive connecting rods, steering knuckles, and various clevis joints. Straddle milling allows for the simultaneous machining of symmetrical faces, ensuring perfect geometric alignment of centerlines in high-volume production.

Industrial Heatsink Arrays

In the production of thermal management components for electronics, side milling with slitting saws can produce dense arrays of deep, narrow fins. The process minimizes kerf loss while maintaining the vertical integrity of fins even at high aspect ratios.

Hydraulic Valve Blocks and Bases

For hydraulic valve bodies, pump housings, and multi-stepped machine bases, gang milling integrates the machining of multiple flats, steps, and grooves. This “single-pass” approach ensures precise relative positioning of complex features across the workpiece.

Large Casting and Forging Peripheries

In the manufacturing of heavy machinery, mining equipment, and marine components, side milling is used for squaring and trimming the peripheries of large castings. Its high torque capacity allows for rapid bulk material removal, establishing high-quality datum surfaces for subsequent finishing.

Conclusion

Side milling is a powerful tool for tackling tough jobs like deep slots and complex stepped parts. It’s steadier and more precise than standard milling, preventing tool drift on difficult cuts and ensuring every part in a large run stays perfectly consistent. If you need a way to improve surface finish while cutting down on production time, side milling is the ideal choice.

Ready to make your machining more precise and efficient? Our technical team is ready to help with expert advice and custom solutions tailored to your toughest production challenges.

👉 [Contact Us Today to Get Started]