In modern manufacturing, all metallic components—from structural steel to precision castings—face the fundamental challenge of corrosion. Unprotected steel rapidly rusts in harsh environments, leading to structural decay and high replacement costs.

To solve this, galvanizing is universally adopted as a robust and cost-effective surface treatment. It creates a durable protective barrier, dramatically enhancing the outdoor durability of steel and extending its service life by decades. This method significantly reduces the lifecycle cost of critical infrastructure in construction, transportation, and energy sectors. This guide provides engineers with a systematic overview of galvanizing’s principles, processes, and applications to support optimal material decisions.

What Is Galvanizing?

Galvanizing is the process of applying a protective zinc coating to steel or iron to prevent corrosion.

This zinc layer blocks moisture and oxygen, and also provides sacrificial protection, meaning the zinc corrodes first to shield the underlying metal.

Cross-sectional view illustrating the principles of hot-dip galvanizing and electro-galvanizing.

In engineering practice, galvanizing is a broad term covering several zinc-coating technologies, including hot-dip galvanizing, electro-galvanizing, thermal diffusion, and zinc-rich coatings..

How Does Galvanizing Prevent Rust?

The effectiveness of galvanizing is based on four key mechanisms that work together to provide long-term protection.

The first is Barrier Protection. The zinc layer forms a dense, impervious physical barrier that isolates the steel surface from corrosive elements like moisture and oxygen. As long as this layer remains intact, the steel cannot rust.

Secondly, Galvanizing utilizes a Sacrificial Anode mechanism. Because zinc is electrochemically more active than iron, when the coating is scratched or damaged, the exposed zinc will preferentially corrode (sacrifices itself) while providing cathodic protection to the exposed steel. This means the protection continues even after surface damage.

Over time, zinc exposed to the atmosphere reacts to form a tough, stable layer of zinc carbonate, known as Patina. This Patina layer is essential for the long-term protection provided by galvanizing, as it slows the consumption rate of the zinc itself.

Finally, in Hot-Dip Galvanizing, the process creates strong Iron-Zinc Alloy Layers that form a metallurgical bond between the zinc and the steel substrate. These alloy layers ensure excellent adhesion and high abrasion resistance, preventing the coating from easily flaking or peeling.

History of Galvanizing

The concept of protecting iron with zinc has been known for centuries, though its industrial application is more recent.

The earliest formal record of using molten zinc for iron protection dates back to 1742, when the French chemist P.J. Malouin presented his findings. This marked the initial observation of what would become the hot-dip galvanizing process.

The industrial breakthrough occurred in 1836, when the French engineer Stanislaus Sorel obtained the first patent for the modern process, which included the use of ammonium chloride flux to prepare the iron surface.

The process quickly gained traction during the Industrial Revolution, as the demand for durable metal infrastructure soared across Europe and North America. Galvanizing became a practical and cost-effective solution for protecting iron and early steel structures.

By the 20th Century, hot-dip galvanizing had become the standardized and mandatory anti-corrosion treatment for structural steel and outdoor components across major engineering standards (such as ASTM and ISO) globally.

Galvanizing Process

The Hot-Dip Galvanizing (HDG) process is a precise, multi-step operation designed to ensure a perfect metallurgical bond and uniform zinc coating.

1.Surface Preparation

Cleanliness is the foundation of quality galvanizing. The process begins with three cleaning steps. First, degreasing uses an alkaline solution to remove organic contaminants like oil and dirt. Second, pickling involves immersing the steel in an acid bath (typically hydrochloric acid) to chemically clean the surface by removing rust and mill scale. Finally, the steel is dipped into a flux solution (zinc ammonium chloride), which cleans the surface of residual oxides and prevents re-oxidation before the component enters the zinc bath.

2.Molten Zinc Bath

The prepared component is slowly immersed into the molten zinc bath. The zinc temperature is strictly controlled at approximately $450^{\circ}\text{C}$. At this temperature, the iron in the steel reacts chemically with the molten zinc, forming multiple layers of strong iron-zinc alloys. These alloy layers are critical for the bond strength and durability of the galvanizing coat.

3.Cooling & Passivation

Once the required coating thickness is achieved, the component is slowly removed, allowing excess zinc to drain. It is then cooled, either by natural air cooling or by water quenching. Sometimes, a passivation treatment is applied immediately after cooling to prevent the formation of “wet storage stain” (white rust), particularly if the component will be stored in humid conditions.

4.Inspection

The final step is inspection. The thickness of the galvanizing coating is measured using non-destructive methods (like magnetic gauges) to confirm compliance with international standards such as ASTM A123 or ISO 1461.

Engineers must account for dimensional changes in precision parts due to the coating thickness; threads and mating surfaces must often be oversized before galvanizing. Furthermore, all enclosed structures must be designed with appropriate vent holes and drain holes to ensure complete zinc coverage and prevent safety hazards during dipping.

Different Galvanizing Methods

While Hot-Dip Galvanizing (HDG) is the industry leader for heavy-duty protection, other galvanizing methods serve specific needs related to component size, dimensional tolerance, and required lifespan.

1.Hot-Dip Galvanizing (HDG)

HDG provides the thickest coating (typically $50 \mu \text{m}$ to $150 \mu \text{m}$) and the longest lifespan (25–50 years). It creates a superior metallurgical bond, offering excellent abrasion resistance and complete internal coverage for pipes and enclosed shapes. It is the standard for infrastructure and structural applications.

2.Electro-Galvanizing

This method uses an electroplating process to deposit a thin layer of pure zinc (typically $5 \mu \text{m}$ to $25 \mu \text{m}$). It offers a smooth, aesthetically pleasing finish and minimal dimensional impact, making it ideal for precision fasteners and indoor components where corrosion risk is low. However, its protection life is significantly shorter than HDG.

3.Cold Galvanizing / Zinc-Rich Paint

Often referred to as Zinc-Rich Paint, this is a coating containing a high concentration of zinc powder. It is not true galvanizing but provides sacrificial protection through conductivity. Its primary engineering use is for repairing damaged HDG coatings in the field (as per ASTM A780) and for small touch-up applications.

4.Thermal Diffusion Galvanizing (Sherardizing)

This method involves heating parts with zinc powder in a sealed drum, creating an all-alloy, highly uniform zinc coating. It is excellent for small, complex parts and threaded components where dimensional stability is paramount, as the coating thickness is uniform and minimizes disruption to mating threads.

| Method | Thickness (μm) | Corrosion Life | Ideal Use | Cost |

| Hot-Dip Galvanizing (HDG) | 50 – 150 | Longest (25-50 years) | Structural Steel, Large Castings | Medium |

| Electro-Galvanizing | 5 – 25 | Short (Indoor/Mild) | Precision Parts, Small Fasteners | Low |

| Thermal Diffusion | 30 – 100 | Excellent | Threaded Components, Small Batch Parts | High |

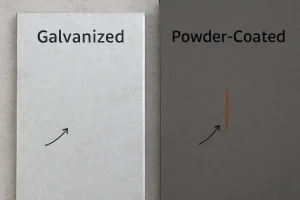

Zinc Coating (Galvanizing) vs. Powder Coating

Zinc coating—commonly referred to in engineering as galvanizing—and powder coating are two widely used corrosion-protection systems, but they operate through fundamentally different mechanisms and therefore serve different engineering purposes.

Galvanizing is a broad category that includes several zinc-coating technologies—such as hot-dip galvanizing (HDG), electro-galvanizing, thermal diffusion galvanizing, and zinc-rich coatings. Regardless of method, galvanizing provides two primary forms of protection:

- Barrier protection, where the zinc layer physically isolates steel from moisture and oxygen; and

- Sacrificial protection, in which zinc corrodes preferentially to protect exposed steel when the coating is scratched or damaged.

Because of this sacrificial behavior, galvanized steel continues to resist corrosion even after minor coating damage. Among all galvanizing methods, Hot-Dip Galvanizing (HDG) delivers the longest outdoor durability, typically 25–50 years in standard atmospheric environments.

Powder coating, in contrast, is exclusively a barrier-type protection system. It offers excellent appearance, uniform color options, and smooth architectural finishes. However, if the coating is chipped, cracked, or otherwise breached, the underlying steel becomes immediately exposed, because powder coating does not provide sacrificial protection.

From a lifecycle perspective, zinc-coating systems (galvanizing) offer superior long-term corrosion resistance, whereas powder coating excels in aesthetics, finish quality, and color control.

For projects requiring both long-term durability and high visual appeal, a duplex system—galvanizing plus powder coating—delivers synergistic performance and is widely used in architectural, transportation, and infrastructure applications.

Benefits of Galvanizing

The widespread adoption of galvanizing is driven by its compelling array of economic and performance benefits, making it an optimal choice for long-term metal protection:

- Superior Long-Term Corrosion Performance: The dual action of barrier and sacrificial protection makes hot-dip galvanizing the industry benchmark, providing maintenance-free protection for decades, significantly increasing the steel structure’s lifespan.

- Low Maintenance Cost: The long service life of the galvanizing coating eliminates the need for repeated painting and maintenance, resulting in a substantially lower Lifecycle Cost (LCC) compared to traditional coatings.

- Full Coverage: As a liquid immersion process, hot-dip galvanizing ensures that every internal space, crevice, and edge receives a uniform coating, eliminating weak points often found in sprayed coatings.

- Abrasion Resistance: The underlying iron-zinc alloy layers are often harder than the base steel. This metallurgical hardness gives the galvanizing coat excellent resistance to mechanical damage, impact, and abrasion during handling and service.

- Sustainable: Galvanized steel is environmentally responsible, as both the steel and the zinc are highly recyclable materials, and the need for frequent maintenance (and the associated VOC emissions from paint) is eliminated.

Limitations of Galvanizing

Although galvanizing offers excellent long-term corrosion protection, the process has several engineering limitations that must be considered during design and manufacturing. These limitations relate to coating thickness control, thermal effects, compatibility with precision parts, and environmental constraints. Understanding these drawbacks helps engineers determine whether galvanizing is appropriate for a given component or if an alternative coating system is more suitable.

Key disadvantages include:

- Dimensional Impact: Coating thickness (especially HDG at 50–150 µm) can affect tolerances, requiring oversizing of threads, machined fits, and precision mating surfaces.

- Thermal Distortion Risk: Hot-dip galvanizing involves ~450 °C immersion, which may cause distortion in thin-walled, large, or asymmetrical components.

- Surface Aesthetics: Galvanized coatings often show spangle, flow marks, or uneven appearance; they are not suitable where high cosmetic uniformity is required.

- Limited Suitability for Complex Geometries: Enclosed structures require vent/drain holes; otherwise, zinc cannot flow freely, and the process becomes unsafe or incomplete.

- Repair Complexity: Once damaged in service, repairs (usually zinc-rich paint) cannot fully replicate the metallurgical alloy layers of HDG.

- Weldability Considerations: Galvanized steel requires additional surface preparation before welding and produces fumes that demand proper ventilation.

- Environmental Conditions: In certain aggressive environments (strong acids, continuous immersion in saltwater), zinc may corrode faster than expected, reducing lifespan.

- Cost vs. Alternatives: For components needing only short-term protection or aesthetic coatings, galvanizing may be more expensive than standard industrial paints or powder coatings.

Applications

Galvanizing is essential across a vast range of industries where long-term exposure to the elements is expected, providing durable protection for critical assets:

- Architectural and Structural Uses: It is the core protective solution for building structural steel in commercial and industrial facilities, bridges, and parking garages.

- Transportation and Infrastructure: Its resistance to harsh weather makes it standard for assets like highway guardrails, traffic barriers, and street lighting columns, relying on hot-dip galvanizing for road safety.

- Power and Communication Towers: Galvanizing is critical for transmission line towers, communication base station structures, and electrical substations, ensuring structural integrity in remote locations.

- Marine Environment Equipment: It is widely used for docks, platforms, and secondary structures, though higher zinc consumption rates must be accounted for in direct marine splash zones.

- Industrial Machinery and Storage Tanks: Galvanized supports, frames, and components ensure operational continuity in corrosive chemical or high-humidity environments.

- Small Fasteners: It is universally applied to small fasteners, such as bolts, nuts, and washers, to guarantee that connection points are as corrosion-resistant as the main structural elements.

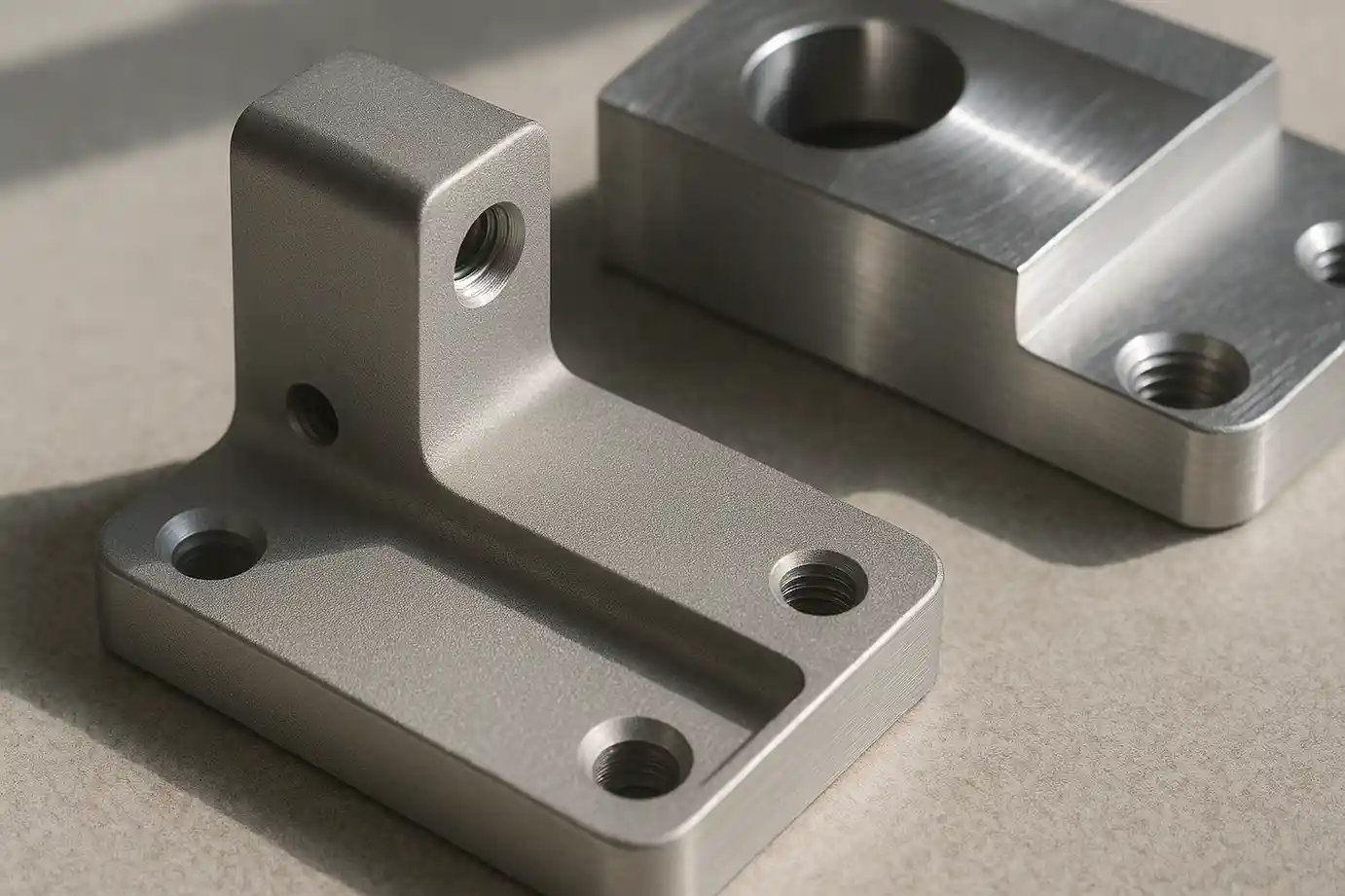

For specialized applications, castings and machined parts that are intended for outdoor use—such as components in pumps, valves, and complex mechanical assemblies—are routinely protected by Hot-Dip Galvanizing or Thermal Diffusion Galvanizing to ensure decades of reliable service.

Galvanizing Grades & “7-Grade Galvanizing”

Galvanizing standards define performance primarily based on the thickness or weight of the zinc coating.

Grades are typically specified by the coating thickness in micrometers ($\mu \text{m}$) or the coating weight per unit area ($\text{g}/\text{m}^2$). Examples from standards include minimum thickness requirements outlined in ISO 1461 and ASTM A123. For continuous products like sheet steel, the grade uses the Z designation; for instance, Z275 indicates a coating mass of $275 \text{g}/\text{m}^2$.

The term “7-Grade Galvanizing” is not a globally recognized or standardized industry grade. This is likely a local or project-specific term and should be avoided in formal engineering specifications, as it is ambiguous.

To ensure quality and compliance, engineers must always specify the precise galvanizing method (e.g., HDG or Electro-Galvanizing), the governing standard (e.g., ASTM A123), and the minimum required coating thickness or weight for the specific component thickness. The chosen grade must be commensurate with the severity of the component’s corrosive environment.

Conclusion

Galvanizing remains one of the most reliable and cost-efficient ways to protect steel in harsh environments. Its combination of barrier protection, sacrificial action, and metallurgical bonding provides long-term corrosion resistance with minimal maintenance.

For engineers, selecting the correct galvanizing method depends on the component’s exposure conditions, structural requirements, and desired service life. Hot-Dip Galvanizing (HDG) continues to be the benchmark for infrastructure and heavy industrial applications.

If your project requires durable outdoor performance, consider specifying the appropriate galvanizing method and coating thickness early in the design phase.

You can also contact our engineering team for support with material selection or coating specifications.

FAQ

How long does a galvanized coating last?

The lifespan of a galvanized coating depends on the zinc thickness and the environment.

Typical hot-dip galvanizing lasts 25–50 years outdoors and even longer in rural areas.

Electro-galvanized coatings are thinner and usually last only a few years in mild indoor conditions.

Marine or industrial atmospheres shorten the service life due to faster zinc consumption.

How to tell if a metal is galvanized?

Galvanized steel often shows:

- A spangled or crystalline surface pattern

- A matte grey or bright metallic finish

- A harder, slightly rough texture from Fe–Zn alloy layers

Engineering identification methods include magnetic coating-thickness gauges, spark testing, or applying dilute acids that react with zinc.

How to remove a galvanized coating?

Common removal methods include:

- Chemical stripping using acids such as hydrochloric acid

- Mechanical removal through grinding, abrasive blasting, or sanding

- Thermal removal, though it is generally avoided due to hazardous zinc fumes

Care is required to avoid damaging the underlying steel.

Can galvanized coating be applied over rust?

Galvanizing cannot be applied directly onto a rusted surface.

Any remaining corrosion products will prevent zinc from forming a proper metallurgical bond with the steel.

For hot-dip galvanizing, the steel must be completely cleaned through degreasing, pickling, and fluxing before entering the molten zinc bath—otherwise the coating will be non-uniform or may fail.

For zinc-rich paint (cold galvanizing), the rust must be mechanically removed (grinding, blasting, or sanding) to achieve a clean, near-white-metal surface. Only after proper surface preparation can the zinc-rich coating provide effective sacrificial protection.