Brass is an engineering alloy composed mainly of copper and zinc, used for valve bodies, pressurized fittings, heat-transfer components, fasteners, and precision-machined parts. Unlike pure copper, brass does not melt at a single temperature. It transitions gradually from a solid to a liquid across a temperature range controlled by its chemical composition and microstructure. Understanding this melting range is essential for foundry control, machining behavior, and alloy selection.

What Is the Melting Point of Brass?

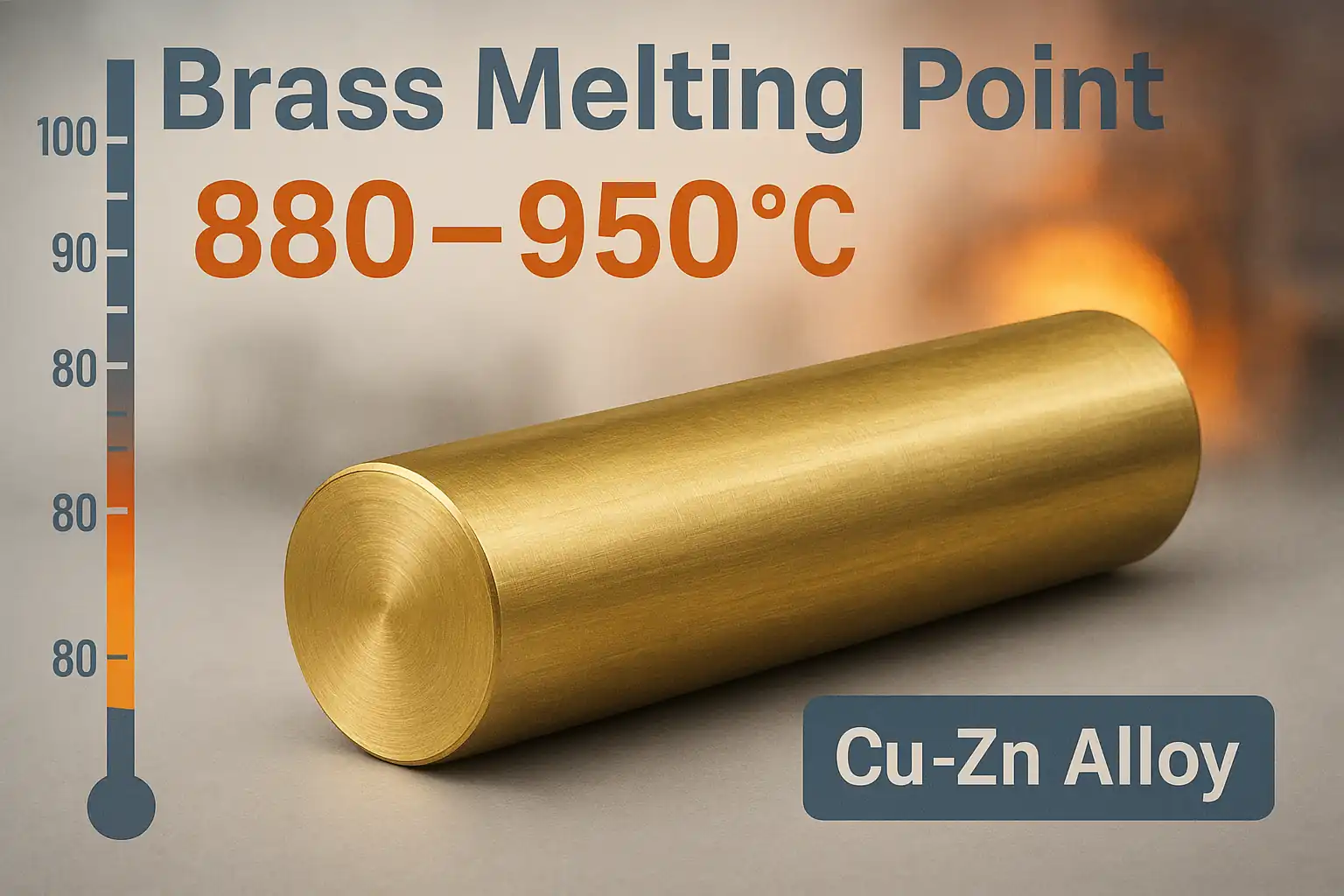

The typical melting range of brass is 880°C–950°C (1616°F–1742°F).

Since brass is a multi-element alloy, it does not fully liquefy at one specific temperature. During heating, its solid and liquid phases coexist within a temperature interval. The exact melting range depends on alloy composition and phase structure, rather than a fixed point value.

Melting Range of Common Brass Grades

- C26000: 925–955°C

- C26800: 900–940°C

- C36000: 870–895°C

- H59: 880–900°C

- C46400: 915–950°C

Higher zinc content lowers the melting range. Free-cutting brasses containing lead have slightly lower melting ranges and provide better machinability, especially in high-volume automated operations. However, alloy choice must also consider pressure requirements, corrosion medium, and service temperature.

How Is Brass Melted in Industry?

Controlled Heating

Brass is typically melted between 950°C and 1080°C (1742°F–1976°F). The goal is not to heat as high as possible, but to reach a temperature window where brass becomes fully fluid without excessive zinc evaporation. Overheating causes zinc loss, altering the designed alloy ratio and reducing sealing capability, corrosion resistance, and final mechanical properties.

Flux and Protective Coverings

Foundries often add flux or protective coverings on the molten surface to suppress oxidation and zinc evaporation. This layer minimizes direct contact with air, stabilizes the alloy composition, and reduces electrochemical reactions during melting. Such protection complements temperature control and is essential for consistent alloy chemistry.

Avoiding Prolonged High-Temperature Exposure

Molten brass should not remain at elevated temperatures for long periods. Excessive time above the melting range leads to significant zinc evaporation, segregation, porosity, and leakage defects after solidification. Industrial practice emphasizes “heat to specification, then pour immediately,” avoiding prolonged hold times at peak temperature.

Refining and Gentle Stirring

Gentle stirring and refining promote uniform microstructure and help inclusions float to the surface, improving density and flow stability. Refining does not mean vigorous agitation; instead, controlled disturbance allows localized segregation to disperse and reduces the risk of shrinkage cavities, gas porosity, or entrapped oxides during casting.

Why Is the Melting Point of Brass Important?

Casting Performance

The melting range governs how brass fills molds. Lower melting temperature improves fluidity, especially useful for thin sections and complex geometries. Poor temperature control, particularly overheating, increases zinc vaporization, segregation, and internal defects, compromising density and pressure retention. Stable melting control is critical for reliable brass castings.

Machining Behavior

Brass exhibits excellent thermal conductivity and moderate melting range, allowing heat to dissipate quickly during machining. This reduces tool wear and cutting temperature, improving dimensional accuracy and surface finish. Lead-containing brasses form easy-to-shear layers, ideal for automated drilling, turning, and milling. In machining, melting behavior correlates with thermal stability at the cutting zone.

Manufacturing Cost

Melting temperature directly affects energy consumption per unit weight. Overheating shortens mold and tool life due to thermal shock, while insufficient temperature leads to cold shuts and misruns, increasing scrap and rework costs. Therefore, the melting range influences casting efficiency, tooling cost, and machining economics.

Factors That Influence the Melting Point of Brass

Alloy Composition

Increasing zinc content lowers the melting range, enhancing castability. Lead improves machinability and slightly decreases melting temperature, promoting chip formation. Tin additions increase corrosion resistance and stabilize microstructure, slightly raising the melting range. Composition determines where the melting window begins and ends.

Microstructure

Even with identical composition, cooling rate and heat treatment change brass microstructure. Alpha brass (α-phase) has a higher melting range and is suitable for pressure-retaining components. Alpha-beta brass (α+β) melts at lower temperature and is easier to deform and machine. Microstructure controls phase transitions, which control melting behavior.

Impurities and Segregation

Iron, silicon, and other impurities widen the melting interval and increase defect risk during solidification. Zinc segregation caused by excessive scrap usage or contamination results in localized early melting, leakage defects, and internal porosity. Oxides and inclusions reduce density and shorten the effective “safe melting window.” Refining is therefore essential for high-performance brass parts.

Melting Point Comparison With Other Metals

| Material | Melting Range (°C) | (°F) | (K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brass (Cu-Zn) | 880–950 | 1616–1742 | 1153–1223 |

| Pure Copper | ~1083 | 1981 | 1356 |

| Bronze | 950–1050 | 1742–1922 | 1223–1323 |

| Aluminum Alloys | 450–660 | 842–1220 | 723–933 |

| Zinc | ~420 | 788 | 693 |

| Magnesium | ~650 | 1202 | 923 |

| Cast Iron | 1150–1200 | 2102–2192 | 1423–1473 |

| Stainless Steel | 1370–1510 | 2498–2750 | 1643–1783 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is brass difficult to melt?

No. Brass is easy to melt, but overheating leads to zinc loss, compromising sealing performance and mechanical strength.

Q: Does brass melt easier than copper?

Yes. Most brass grades melt at significantly lower temperatures than pure copper.

Q: Which melts easier, brass or aluminum?

Aluminum melts at a lower temperature, but does not perform well under pressure, so it cannot replace brass in sealing or valve applications.

Conclusion

The melting point of brass is not a single value, but a range influenced by alloy composition, microstructure, and impurities. This range affects casting quality, machining performance, tool life, and overall manufacturing cost. In practice, melting behavior should be evaluated together with corrosion environment, pressure rating, and machining method to ensure proper alloy selection.

If you need assistance selecting a brass grade for a specific operating pressure or medium, feel free to send your drawings for engineering support.